Why do some people live to 100 while others die decades earlier? Most of us have heard the same explanation for years: eat well, exercise, avoid smoking, get lucky. Lifestyle, environment, and chance were thought to do most of the work.

A new study led by molecular biologist Uri Alon at the Weizmann Institute of Science challenges that picture in a big way. Published in Science, the research suggests that our genes may explain up to 55% of the differences in how long people live — far more than previous estimates, which ranged from as little as 6% to about 33%.

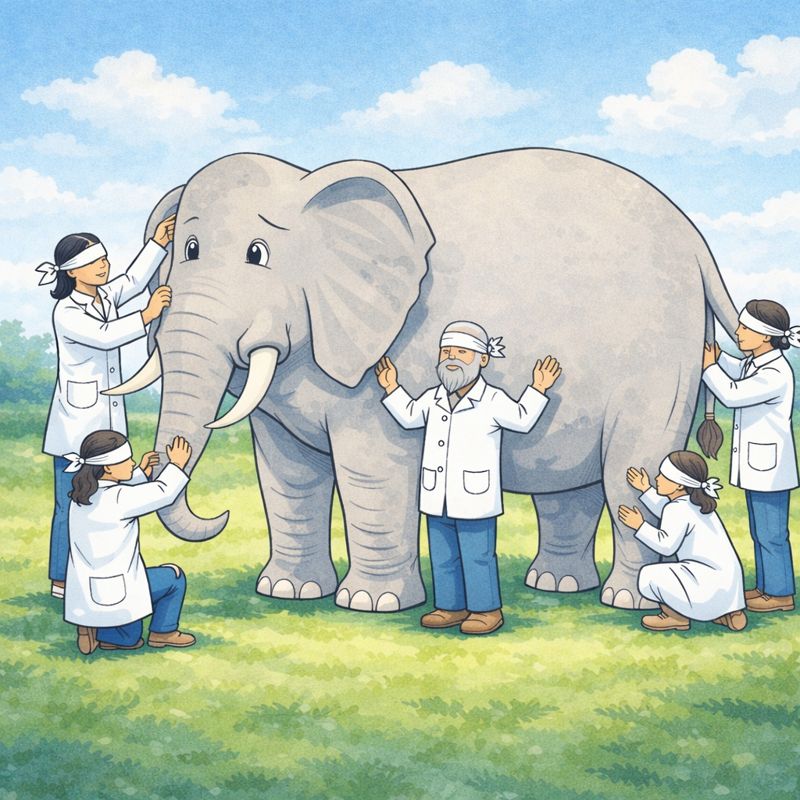

The key idea is simple but powerful: not all deaths are the same.

Some people die because of “external” causes — accidents, infections, violence, pollution. These are called extrinsic deaths. Others die because their bodies gradually wear down with age — intrinsic deaths, tied directly to the biology of aging.

Earlier studies did not clearly separate these two. Many relied on people who lived in the 1800s or early 1900s, when infections and accidents were much more common. That made it look as if genetics played a smaller role than it really does.

Alon’s team reanalyzed large datasets of twins from Denmark and Sweden — identical twins who share all their DNA, and fraternal twins who share about half — along with siblings of American centenarians. In total, they studied nearly 16,000 related pairs. They also looked at twins raised apart, so they could remove the effect of growing up in the same environment.

When the researchers statistically removed deaths caused by external factors, a different picture appeared: the genetic influence on lifespan steadily rose to about 55%.

This matches what scientists already see in lab animals and in other human traits, like metabolism or cognitive ability, where genetics plays a large role.

The study also found that genes matter differently depending on the cause of death. Genetics accounted for about 30% of cancer deaths at all ages. For heart disease, the genetic role was around 50% in younger people. For dementia-related deaths, it was even higher — up to 70% around age 80.

Researchers asys this work helps correct a long-standing misunderstanding. He has spent years studying families of people who live past 100. His data show that if both your parents are centenarians, you are likely to live about 24% longer than average. Even having one long-lived parent or grandparent noticeably increases your chances.

So does this mean lifestyle doesn’t matter? Not at all.

If genes explain about half of the differences in lifespan, the other half still depends on external factors — many of which we can influence. Diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol, and exposure to toxins still shape how our lives unfold. But this study suggests that we don’t start from the same baseline. Some people are simply born with bodies that age more slowly.

Scientists say this finding has important consequences. If genes play such a large role, it becomes even more important to identify the specific genetic variants and biological pathways that control aging. That could one day lead to treatments that help more people age the way today’s centenarians do.

In short, living a long life is not just about what you do. It’s also about what you were born with.

Ben Shenhar et al. ,Heritability of intrinsic human life span is about 50% when confounding factors are addressed.Science391,504-510(2026).DOI:10.1126/science.adz1187